He was the chronicler of the losers and persecutors of all time – Imre Gyöngyössy was remembered in Budapest | Hungarian Courier

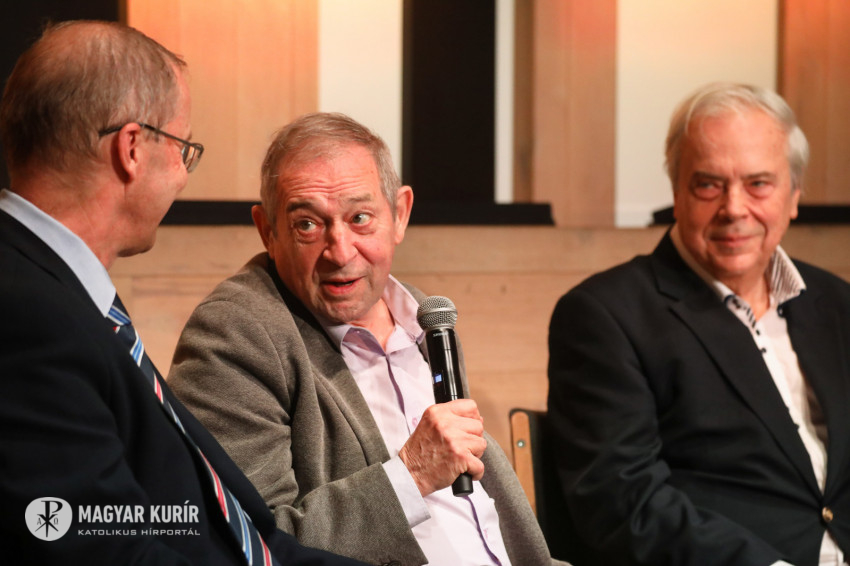

After the screening, a discussion took place, attended by two former co-creators of Gyöngyössy: his widow, art historian Katalin Petényi and film director Imre Kabay, Bishop Astrik Várszegi, Archbishop Emeritus of Pannonhalma and Tamás Jordán, Actor of the Nation, theater directors. The discussion was moderated by Antal Molnár, Director of the Institute of History of the Research Center for the Humanities.

The participants were greeted by Antal Molnár. He reminded him that Imre Gyöngyössy had moved from a small village in South Transdanubia to Pannonhalma in 1940, the son of a doctor from Étrény, to a grammar school targeting what was then an elite training, which provided a cultural and spiritual impetus for life. Forty-five years later, the director of BTK TTK joined the same educational institution, which is very famous for its film club, as it is run by the Benedictine teacher Pintér Ambrus, the oldest cinematographer in the country, for decades. Antal Molnár saw less than a hundred films as a high school student in Pannonhalma, but very few remained in him really deep, as reproducible series of images in his head. Very very few films included the Rebellion of the Oscar-nominated Job, of which he said, “Perhaps the most defining film experience of my student age. It was already noticeable at that time that we did not know of any other film from the director, who was said to be a student from Pannonhalma, we did not even hear about it, although it was obviously not his only film. ”Later, getting to know the other works of Imre Gyöngyössy, he was captivated by his deeply empathic stand for the generalized, the suffering, the almost obsessed sense of duty, the news about the last traces of the doomed communities, people and cultures.

Antal Molnár quoted the well-known saying: history is written by the winners. But he added: the real art is back to the losers. Imre Gyöngyössy is the chronicler of the losers, with this consciously chosen role he himself could not win in Hungary of the Kádár era. His poetry and films, fueled by his prison experiences, his very positive memento film post and documentary about the Gypsies living on the periphery of society, have elicited the dislike of the official censors and tellers of the era. led after 1980. One of Gyöngyössy’s 1985 interviews with the director of the research center of the Institute of History was particularly catchy, which stated: “Free societies are responsible for the interaction of knowledge personalities and the human rights community from birth to others.”

According to Antal Molnár, the art of the poet-film director makes us more European Hungarians, more Hungarian Europeans, and for the generalized, the losers of history, in fact, an almost obsessed exhibition and commitment may bring us closer to understanding the essence of Christianity.

Antal Molnár, who led the conversation, also said that the Hope and myth watching is always a fantastically great experience. – What is the secret that foreign – Italian, French, English, American – film experts fantastically understood Imre Gyöngyössy’s films? he asked.

Katalin Petényi explained: her husband ‘s first feature film, Flower Sundayot in 1968, which was a great success in Europe. Before that, however, he wrote a beautiful screenplay from his prison experiences, Guitar sound in the rain he wanted to hold this. This poetic, visionary story takes place in prison, the main motives for friendship and sacrifice.

Perhaps the historical sensitivity of Central Europe was felt by Western European critics and festival directors, which was a new thing in Europe. This was characteristic not only of Imre, but also of Tarkovsky, Zanussi, who was discovered at the time, said Katalin Petényi. – It was a new voice in European cinema. Imre’s choice of subject and commitment were coupled with a special spiritual commitment and a very strong ballad tone. It was extremely important for him to survive the myth in the present, to depict the archaic peasant world that Flower Sundaycan also be seen in. Or the struggle, the relationship between the individual and the community, history, and then the basic human relationships — mother, son, siblings, friendship, love — all that gives moral strength have all been noticed in the West as well.

Imre Gyöngyössy’s widow also highlighted her husband’s special faith, which strengthens hope and love in people.

Archbishop Astrik Várszegi emeritus of Pannonhalma also said, as a scholar researcher of the Benedictine order, in 1940, when ten-year-old Imre Gyöngyössy came to Pannonhalma as a student, they still had a grammar school in Italian. with students. Astrik Várszegi pointed out that the prefect of the child was Gyöngyössy Gellért Békés, with whom they loved each other very much, it was his definition of his person throughout his later life. Father Astrik also met Imre Gyöngyössy through Gellért Békés.

It was said in the conversation that Tamás Jordán did not study acting, he has a degree in earth engineering. He was a member of the legendary University Stage in the 1960s and played the Baroque passion in the Gyöngyössy poetic drama. In the ensuing period, he pondered leaving the acting career and continuing to work as an engineer. At that time, in 1970, the Twenty-Fifth Theater was established. Tamás Jordán yellow an unexpected phone call from the management of the new theater that he saw him on the University Stage in the drama of Imre Gyöngyössy and was asked to undertake the Socrates’ defense speech the one-sentence role of the prison servant. He said yes, and since then he has been given more and more theatrical assignments, i.e. Baroque passion meant the seal of his acting profession. Tamás Jordán later worked with Imre Gyöngyössy, and watching his face, his gaze, his absolute sincerity, he was interested in the other person, as if asking: Do you know anything more about the figure you are playing than there is in your text about him? With this mentality, he lured the actor to the maximum.

Kabay Barna added that it was the same in Imre Gyöngyössy’s eyes as in his soul, and this was felt by everyone during filming, from the make-up artist to the actor. He saw the shooting as a real team effort, living with the crew all along.

The solid faith of Imre Gyöngyössy is well illustrated by The wisdom of Job poem entitled Job’s rebellion recommended to her female protagonist, Hédi Temessy: / We all fall backwards / fall on the worn-out threshold of the chased. / But step by step we are always / there behind us / our creator if we fall. “

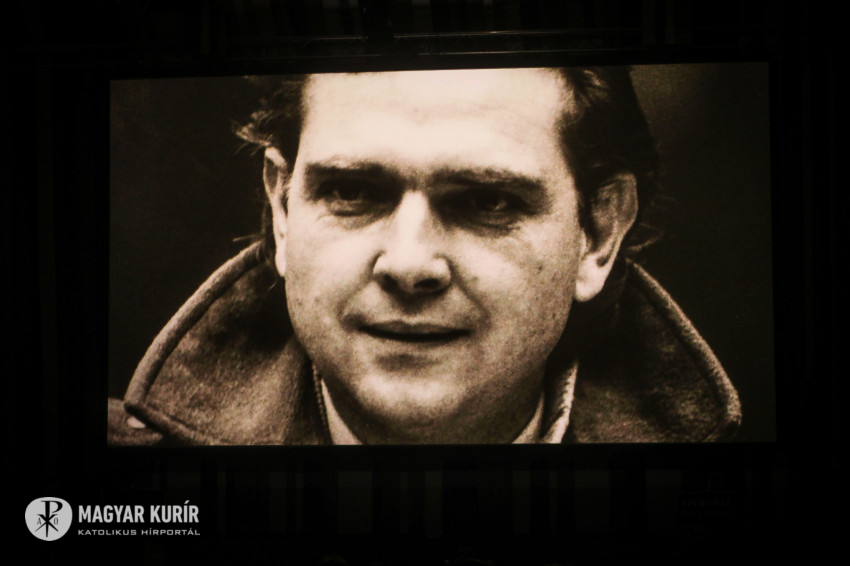

Imre Gyöngyössy was born in 1930 in Pécs. He spent his childhood in a small village in Transdanubia, Értény, where his father was a doctor. The myth, the archaic peasant world, the ancient rites, the experience of people living in harmony between nature and community accompanied him throughout his life. At the age of ten, he was admitted to the Benedictine Grammar School in Pannonhalma, where he learned Italian at his native level. She grew up reading Dante and Petrarca. It has become an inexhaustible source and inspiration for the entire oeuvre of Italy’s intellectual and cultural heritage.

He was arrested in 1951. In a conceptual lawsuit, he was sentenced to three years in prison, ten years in disqualification from public affairs, and total confiscation of property on a fabricated charge of conspiracy against the state. He was released from prison with serious illness.

In 1956 he was admitted to the College of Theater and Film Arts, where in 1961 he graduated as a film writer and film director. His first feature film, Flower Sunday brought him international fame. Foreign critics greeted the first film director with the greatest appreciation, referring to the Italian newspapers as “Hungarian Pasolini”.

“In his later feature and documentary films, Gyöngyössy explored the limits and infinity of freedom. I am interested in birth, death, rebirth, the poetry of myths, the basic human relationships: friendship, love, mother, meeting boys and testers, the self-conscious man, history and the personal drama of each person. ”(Katalin Petényi director, screenwriter).

From the end of the seventies with his co-creators, Barna Kabay and Katalin Petényi, she made films on different continents about exiles, homeless people and people deprived of their human rights. His films were screened with great success at the most prestigious international film festivals in the world, he was awarded prizes, but in Hungary he was in the crossroads of the State Defense Services for a long time, only before his death, in 1994, he was rehabilitated.

Author: Dániel Bodnár

Photo: Zita Merényi

Hungarian Courier